Infrastructure Week 2024

Urban Jungles: How Birds Thrive in City Settings

When we think about urban environments, images of bustling streets, towering skyscrapers, and dense human populations come to mind. Yet amidst this concrete jungle, a surprising array of bird species not only survive but thrive. Adapting to city life involves a fascinating blend of biological resilience and behavioral flexibility, allowing birds to exploit new resources and navigate the challenges of urban spaces.

Among the most iconic urban dwellers is the Peregrine Falcon. Renowned for being the fastest animals on earth—capable of diving at speeds over 200 miles per hour to catch their prey—these cosmopolitan raptors have found a surprising ally in tall buildings and skyscrapers. These structures mimic the high cliff ledges Peregrine Falcons traditionally nest on. Cities also provide an abundant supply of prey such as pigeons and smaller birds. Major cities around the globe, from New York to London, now host thriving populations of these falcons, which have adapted remarkably well to urban life.

Streaming nestcams featuring Peregrine Falcons are abundant due to their frequent use of urban buildings for nesting. Right now is a great time to check out cams like the ones linked below, as the Peregrines are busy raising their fluffy young.

Then there are Barn Swallows, who traditionally nest in caves, and in barns and other open structures in rural areas. In cities, these agile fliers have transitioned to nesting under bridges and highway overpasses, using these man-made structures to support their mud-built nests. This adaptation not only provides them with safe nesting sites away from many ground predators, but also places them near water sources where insects—their primary food source—are abundant.

Other bird species that thrive in areas of human development are easy to identify: a big clue is in their name (the name we humans gave to them). Think about where we can find birds like House Sparrows, House Finches and House Wrens, Barn Owls, Roadside Hawks, and House Martins of the Old World.

City parks and gardens are vital refuges for many bird species. Here, smaller birds like sparrows and finches find not only food in the form of plants and insects but also an assortment of bird feeders filled by enthusiastic bird watchers. These green spaces serve as miniature ecosystems within the urban sprawl, offering shelter and breeding sites. The presence of trees and water features in parks also supports a variety of bird species, from the common robin to the more elusive kingfisher in cities with rivers or ponds.

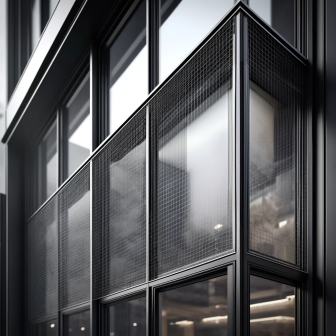

Birdhouses and nesting platforms are another crucial element that bolsters bird populations in urban settings. Many cities have seen successful implementation of nest box programs that encourage species such as Eastern Bluebirds and Purple Martins to take up residence. These initiatives not only help in bird conservation, increase biodiversity and promote a healthy environment, but also engage the local community in wildlife management and education. Platforms and artificial nests provide safe havens for birds to rear their young away from the prying eyes of predators and the disturbances of city life.

Moreover, urban environments are witnessing innovative approaches to support bird life. For instance, some cities have introduced green roofs, which are covered with vegetation and provide a new habitat for urban birds and other wildlife. These green roofs can reduce the "heat island" effect of cities and offer birds a cooler place to rest and feed. They also help in water retention and provide foraging grounds for insects, thus supporting a small but vital food web for urban bird species.

In adapting to urban environments, birds demonstrate remarkable versatility and resilience. While these adaptations highlight their ability to cope with and exploit new environments, they also underscore the importance of human efforts in supporting urban wildlife. By installing birdhouses, maintaining parks, and initiating conservation programs, we can ensure that our cities remain hospitable to a diverse array of bird species.

.jpg)